Incoterms® 2020

As per January 2020, a new set of Incoterms® 2020 will become active. This is a set of trade terms which describe:

- Obligations: Who does what in organizing the carriage, insurance of goods, obtaining shipping documents, arranging for export or import licenses;

- Risk: Where and when the seller delivers the goods, in other words where does the risk transfers;

- Costs: Which party is responsible for which costs

The Incoterms® 2020 cover these areas in a set of ten articles for each term, numbered A1/B1, etc. “A” terms for the Seller and “B” terms for the Buyer.

In this article, I do not aim to discuss all the rules, but will focus on answering 7 important questions:

- Why better not use EXW or DDP?

- Why a change from DAT to DPU?

- Why is the use own means of transport relevant for FCA, DAP, DPU, and DDP?

- Why do we have different levels of insurance in CIP and CIF?

- Why is a “Bill-of-Lading On-board notation” added for FCA?

- Why do we still need separate maritime terms like FAS, FOB, CFR, and CIF?

- Why is it important how we mention Incoterms®?

By answering the why’s you will get familiar with the differences between the previous version and gain more insight into the updated Incoterms® 2020 framework as well.

Incoterms® 2020

7 why’s explained for Incoterms® 2020

1. Why better not use EXW or DDP?

There are two rules at the extreme end and therefore easily be chosen. The buyer wants DDP and the seller EXW. For sure, it minimizes the risk for one party. But the other party might face some issues which couldn’t oversee at the moment of the agreement.

With EXW the seller makes the goods available at his dock (or another pre-defined place). Furthermore, the seller has to load the goods and take care of the transportation and export formalities. Parties often agree to apply EXW, but in practice, the seller is arranging transport, export formalities and loading on behalf of the buyer. But what if it goes wrong? The seller isn’t liable, and the buyer has to absorb all the costs and consequences. That is why it is better to agree on FCA, even the place of delivery is on the sellers’ dock.

On the other hand, as a buyer we like DDP. But there is something similar. Although the seller is not responsible for unloading, he is responsible. for import formalities and becomes in a lot of cases the importer of the record too. That means that he becomes liable for all product issues which might occur in the country the product is delivered. In a lot of cases, the seller is physically or legally difficult to carry those obligations. It would be better in those cases to sell the goods under DAP or DPU rules.

But when both EXW and DDP seems to have side effects, why are they still used? First, it can be in the calculation of the factory gate price (EXW) or landed costs (DDP). Secondly, in domestic trade or when you are in the same Customs Union, there are no obligations on customs formalities. In those cases, both rules can be having value.

You can also have a look at below guide.

Guide to international commercial terms in Import-Export business2. Why a change from DAT to DPU?

In Incoterms® 2010 the only difference between DAP and DAT was that in DAT the goods were delivered unloaded, whereas in DAP, the seller delivered the goods when the goods were placed at the disposal of the buyer on the arriving means of transport for unloading. The main difference was, therefore, loaded or unloaded.

In the Incoterms® 2020 version there are two changes made with regard to the rule DAT:

- DAP appears now before DAT as this reflects better the actual situation. In DAP still loaded and in DAT unloaded.

- The second change was the change of the acronym DAT into DPU, emphasizing the reality that a place could be any place and not only a terminal.

In the case of DPU the seller is responsible for export, but not for any import formality including post-delivery transit through third countries. If the buyer fails, in this case, to take off the import formalities, he bears the risk of loss and damage and cost for holding the goods at the point of entry, because delivery hasn’t occurred yet. In those situations, you might consider DDP.

As mentioned, the main difference between DAP and DAT is the unloading. Remember that this might be crucial in the situation where there is a significant risk of damage during unloading the goods. Also, when special unloading equipment is needed, the difference between the two terms might be relevant.

3. Why is the use own means of transport relevant for FCA, DAP, DPU and DDP?

In Incoterms® 2010 it was assumed that the goods were to be carried by a third party engaged for the purpose. Who was responsible for arranging it, was dependent on the rule used.

There can be many reasons why we collect or bring goods or arrange a transportation contract ourselves. Although it is common practice, Incoterms® 2010 didn’t foresee that situation. It did only mention ”to contract” which means there should be a transportation contract. This is – formally speaking – not the case with its own means of transportation. In the new rules, this is corrected by using the description “… the buyer/seller must contract or arrange at its own cost for the carriage of goods to the named place of destination or to the agreed point …”

4. Why do we have different levels of insurance in CIP and CIF?

Most of you will have the understanding that the delivery takes place and risk transfers with CIF and CIP rules at the moment of loading at the carrier. Next to that, the insurance will cover for damages and losses up until to moment of actually arriving at the place agreed. So, if something happens with the goods I am covered for the losses.

The reality, however, is that the insurance was only covering general average and salvage charges incurred to avoid loss from any cause except those excluded. In practice, this was a very minimal coverage, of which not all parties are aware. This is the so-called “Clause C” insurance.

In preparation for the revised Incoterms® 2020 it has been an option to move forward to a Clause A obligation, thus increasing the cover obtained by the seller to benefit the buyer. The “Clause A” coverage can be seen as “All Risk” (with exceptions).

TYPE OF RISK |

MARINE CARGO CLAUSES |

|||

A |

B |

C |

||

| 01 | Fire / Explosion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 02 | Stranding / Sinking | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 03 | Barratry / Jettison | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 04 | Collision | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 05 | General Average / Sacrifice | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 06 | Earthquakes | ✓ | ✓ | X |

| 07 | Washing overboard / Entry of water into ship | ✓ | ✓ | X |

| 08 | Theft / Pilferage / Non-delivery | ✓ | X | X |

| 09 | Malicious damage | ✓ | X | X |

| 10 | Shortage | ✓ | X | X |

| 11 | Contamination / Heavy weather | ✓ | X | X |

| 12 | Delay | X | X | X |

| 13 | Spontaneous combustion (self-heating) | X | X | X |

| 14 | War / Strikes / Civil Instability | X | X | X |

| 15 | Terrorism / Piracy | X | X | X |

Nevertheless, it has been decided to provide for two minimum coverage options within CIP and CIF, either Clause A or Clause C.

- When opted for the default “Clause C” coverage, the term maritime term CIF should be used.

- Outside the maritime world, the default coverage will be “Clause A”, reflected in the rule CIP.

To make life easier, in the sales contract a higher (CIF) or lower (CIP) levels of coverage can be agreed. So, when using these rules, there is still a negotiation between the buyer and the seller needed. In both situations, the insurance shall cover, at a minimum, the price provided in the contract plus 10% (i.e. 110%) and shall be in the currency of the contract.

&vnbsp;

5. Why is a “Bill-of-Lading On-board notation” added for FCA?

When goods are sold FCA for carriage by sea, sellers or buyers – or more likely their banks – may require a Bill-of-Lading (B/L) with an on-board notation. However, delivery under the FCA rule is completed before the loading of the goods on board of the vessel. Under Incoterms® 2010 in case of FCA it is by no means certain that the seller can even obtain an on-board Bill-of-Lading from the carrier. This carrier is likely, under its contract of carriage, bounded and entitled to issue an on-board Bill-of-Lading only once the goods are actually on-board.

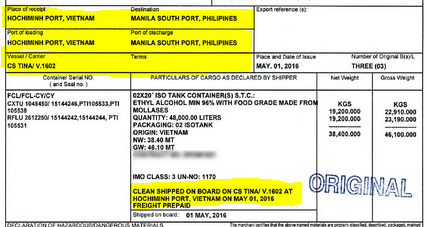

But what does the on-board B/L mean? It is a form of evidence that a clause of the Letter of credit (L/C) has been fulfilled. For example, a L/C requires:

– Full set of original Bill of Lading

– Port of Loading: HOCHIMINH CITY, VIETNAM

– Port of Discharge: MANILA SOUTH PORT, PHILIPINES

To provide the evidence the bill of lading will require, an on-board notation showing any vessel name, the port of loading “Hochiminh City, Vietnam” and the on-board date. The statement

CLEAN SHIPPED ON BOARD ON CS TINAI V.1602 AT HOCHIMINH PORT, VIETNAM ON MAY 01, 2016. FREIGHT PREPAID

on the B/L in combination with the destination port MANILA SOUTH PORT, PHILIPINES gives the evidence that the goods are delivered correctly.

As especially for shipping containerized cargo it is advised to use the FCA term instead of the maritime FOB, Incoterms® 2020 now provides, for this demonstrated need in the marketplace, a somewhat optical solution. Under FCA the buyer and the seller can now agree that the buyer will instruct its carrier to issue an on-board B/L to the seller after the loading of the goods.

6. Why do we still need separate maritime terms like FAS, FOB, CFR and CIF?

Maritime transportation exists since ages, and all harbors and ports have in established an extensive set of (local) rules and regulations, collected into Maritime Law. This is a body of laws, conventions, and treaties that govern private maritime business and other nautical matters, such as shipping or offenses occurring on open water and includes international rules, governing the use of the oceans and seas (Law of the Sea). Maritime Law also governs many of the insurance claims relating to ships and cargo; civil matters between shipowners, seamen, and passengers; and piracy. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is responsible for ensuring that existing international maritime conventions are kept up to date, as well as developing new agreements as and when the need arises.

In 1936 the first set of Incoterms® was published and aimed to be easy to understand by all the participants in order to prevent misunderstandings, disputes, and litigation. Not surprisingly, this first set was focused on maritime traffic, and consist of the rules FAS, FOB, C&F, CIF, Ex Ship, and Ex Quay.

As from the eighties, with the expansion of carriage of goods in containers and new documentation processes, the need came for another revision. This edition introduced the trade term FRC (Free Carrier…Named at Point), which provided for goods not actually received by the ship’s side but at a reception point onshore, such as a container yard. This was also the start of separation of the rules for maritime and other transport modes. This separation was included in the complete revision of the Incoterms® in 1990.

Nowadays, the “transport by sea or inland waterway only” rules should only be used for bulk cargos (e.g. oil, coal etc.) and non-containerized goods, where the exporter can load the goods directly onto the vessel. When the goods are containerized, the “any transport mode” rules are more appropriate.

As the Maritime Law has its own traditions and history, this justifies the need for specific maritime rules. Take for instance the difference in the CIF and CIP rule. The risk coverages clauses are those which originated from the Maritime Cargo. Another one is the loading of a ship. This is more cost and time-intensive and therefore needs its own set of rules, like FAS and FOB. The difference between CPT and CFR is that in the first rule the goods are handed over to the carrier and in the CFR the delivery of the goods is on-board of the ship. A critical difference in the point at which risk transfers from seller to the buyer. Let’s imagine the cost and risk impact in case of bulk cargo and non-containerized goods in case something went not as intended.

7. Why is it important how we mention Incoterms®?

It is important to know that Incoterms® is not a generic name for any international trade terms, but is a trademark used to brand the Rules devised by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). In the United States of America, a different set of trade terms is in use for domestic transportation. These Freight Terms are specified in the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC). Delivery is according to the UCC, an intangible concept and occurs when and where the seller voluntarily transfers effective ownership of goods to the buyer. Once delivered, the rights of ownership and risk of loss rest with the buyer. This is different from the receipt which occurs when the buyer takes physical possession of the goods. It is in the buyer’s interest to carefully negotiate freight terms as the UCC favors the seller when terms are not specified. But it is also fundamentally different from the concept the ICC uses.

The most common UCC terms are:

- Free on Board (FOB) place of shipment or shipment contract

- Free on Board (FOB) place of destination or destination contract

- Free on Board (FOB) vessel, car, or another vehicle

- Free Along Side (FAS) vessel (watercraft)

But in the UCC terms, there are a lot of variations in use. One major difference is that the UCC rules look at the transfer of ownership, where the ICC Incoterms® look at delivery, cost, and transfer of risk. The transfer of property/title/ownership of goods being sold, is NOT dealt with.

The visual similarity of terms, but the major differences is where the confusion starts. The confusion of used rules in international trade – with all legal implications – is easily being made. Therefore, it is extremely important to use the Incoterms® in the correct way: Meaning that you always have to use exact the following notation:

- The chosen Incoterms® Rule name,

- The named port, place of destination or to the agreed point

- Incoterms®

- Year of issue

A correct notation therefore is:

- FCA 33 Avenue Président Wilson, Paris, France, Incoterms® 2020

- DAP N0 123, ABC Street, Portland, Incoterms® 2020

- FOB Rotterdam, Incoterms® 2020

- CIF Shanghai, Incoterms® 2020

You might think, why adding the year of issue. The previous versions of Incoterms® are still in use. The ICC did not withdraw them. It might be for some companies that they still want to use a previous version because the new version is not serving them well. This is allowed, but not common. A more common reason is now with the introduction of the new version. Which one is intended, the 2010 or Incoterms® 2020?

In this article, an insight is given regarding the changes of Incoterms® 2020. Please refer to the official publication for the exact meaning and obligations related to the use of any of the Incoterms® 2020 rules.

You want to know the basic of foreign trade management, then LIFETIME BASICS OF FOREIGN TRADE MANAGEMENT – 3 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW

About the author:

Paul Denneman MSc CLTD CPIM CSCP, is a supply chain expert and international master trainer in APICS Certification Programs like Certified in Logistics, Transportation and Distribution (CLTD). He is observing changes in supply chains for the past 25 years.

Want have more insights, please visit www.mutatis-mutandis.com or connect on LinkedIn

Copyright notice.

Incoterms® and the Incoterms® 2020 logo are trademarks of ICC. Use of these trademarks does not imply association with, approval of or sponsorship by ICC unless specifically stated above. The Incoterms® Rules are protected by copyright owned by ICC. Further information on the Incoterms® Rules may be obtained from the ICC website iccwbo.org.